Weetamoo

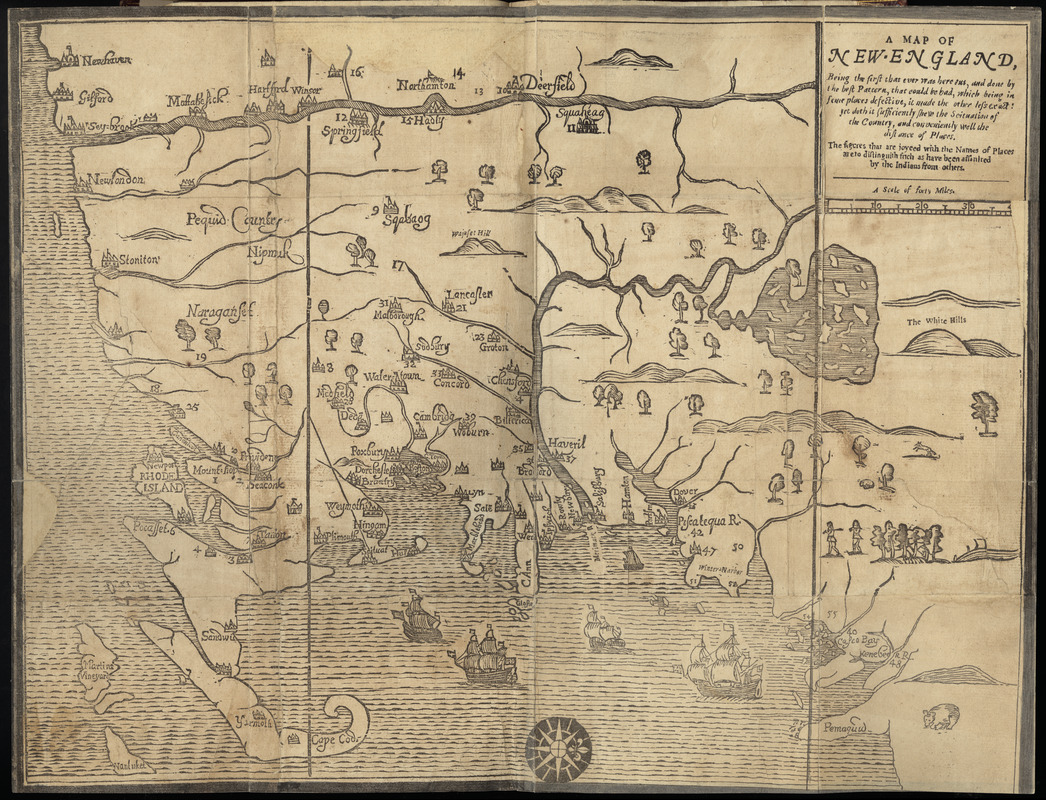

The Pocasset Wampanoag Tribe, part of the Pokanoket Nation, are indigenous people of modern-day Rhode Island and Massachusetts.1 During the King Philip’s War (1675-1678), the Pocasset joined King Philip, also known as Metacom, fighting against the English and their Native American allies.2 At the time they were led by Sachems.

Weetamoo was the Pocasset Sachem, and an influential, clever leader during the King Philip’s War.3 She was a diplomat and ruler with a powerful army. When war broke out, she was the first ally that King Philip sought.4 The English forces she fought were very aware of Weetamoo’ s strength as well, based on their reports from the colonies.5

Most of the surviving information about Weetamoo comes from the writings the English colonizers she led the fight against. Puritan captive, Mary Rowlandson, and clergymen who chronicled the war, William Hubbard and Increase Mather wrote about Weetamoo from an English perspective.6 Their words show respect for her capability but are also affected by European biases about race and gender.7

Despite her tactical use of the land and her understanding of the English, Weetamoo died in battle. The English ultimately killed King Philip and won the war. The respect and admiration she had from the people she led, however, shows the success of Weetamoo’s leadership.8

Ephemera

These objects are ephemera from the Wampanoag people group, which the Pocasset people are a part of, during the time which Weetamoo would have been alive.

-

The Sudbury BowFrom Peabody: Made from hickory, the bow measures over 5 feet high. An inscription on the bow reads: "The bow was taken from an Indian in Sudbury, Masstts A,D, 1660 by William Goodnough, who shot the Indian while he was ransacking his house for plunder." This description was interpreted literally, resulting in the title “The Sudbury Bow.” While the Indigenous maker of the bow is unknown, it is believed to be one of the only surviving examples of a seventeenth-century Native American bow. The bow was also used as inspiration for the bow depicted on the 1898 Seal of Massachusetts.

The Sudbury BowFrom Peabody: Made from hickory, the bow measures over 5 feet high. An inscription on the bow reads: "The bow was taken from an Indian in Sudbury, Masstts A,D, 1660 by William Goodnough, who shot the Indian while he was ransacking his house for plunder." This description was interpreted literally, resulting in the title “The Sudbury Bow.” While the Indigenous maker of the bow is unknown, it is believed to be one of the only surviving examples of a seventeenth-century Native American bow. The bow was also used as inspiration for the bow depicted on the 1898 Seal of Massachusetts. -

Belt -- Shown with the So-called King Philip Belt number 49333

Belt -- Shown with the So-called King Philip Belt number 49333 -

"King Philip's" bowl, Wampanoag Indians

"King Philip's" bowl, Wampanoag Indians -

String of Wampum and Glass Beads

String of Wampum and Glass Beads

Books

The Soveraignty & Goodness of God

This book was written by Mary Rowlandson, a captive of Weetamoo, and shows the European understanding of Weetamoo's role as a leader and a woman.

Notes

- Lisa Brooks, “‘Every Swamp Is a Castle’: Navigating Native Spaces in the Connecticut River Valley, Winter 1675–1677 and 2005–2015,” Northeastern Naturalist 24 (2017): 49.

- Gina M. Martino-Trutor, “‘As Potent a Prince as Any Round About Her’: Rethinking Weetamoo of the Pocasset and Native Female Leadership in Early America,” Journal of Women’s History 27, no. 3 (Fall 2015): 37, https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2015.0032.

- Lisa Brooks, “Turning the Looking Glass on King Philip’s War: Locating American Literature in Native Space,” American Literary History 25, no. 4 (2013): 723; Tiffany Potter, “Writing Indigenous Femininity: Mary Rowlandson’s Narrative of Captivity,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 36, no. 2 (2003): 155; Brooks, “‘Every Swamp Is a Castle,’” 9.

- Martino-Trutor, “‘As Potent a Prince as Any Round About Her,’” 37, 38; Brooks, “‘Every Swamp Is a Castle,’” 7.

- Potter, “Writing Indigenous Femininity,” 155; Martino-Trutor, “‘As Potent a Prince as Any Round About Her,’” 44.

- Potter, “Writing Indigenous Femininity,” 2; Martino-Trutor, “‘As Potent a Prince as Any Round About Her,’” 37.

- Potter, “Writing Indigenous Femininity,” 163; Brooks, “Turning the Looking Glass on King Philip’s War,” 727.

- Martino-Trutor, “‘As Potent a Prince as Any Round About Her,’” 37, 38.

Suggested Scholarship

Brooks, Lisa. “‘Every Swamp Is a Castle’: Navigating Native Spaces in the Connecticut River Valley, Winter 1675–1677 and 2005–2015.” Northeastern Naturalist 24 (2017): H45–80.

———. “Namumpum, ‘Our Beloved Kinswoman,’ Saunkskwa of Pocasset: Bonds, Acts, Deeds.” In Our Beloved Kin, 27–71. A New History of King Philip’s War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018.

———. “Turning the Looking Glass on King Philip’s War: Locating American Literature in Native Space.” American Literary History 25, no. 4 (2013): 718–50.

Martino-Trutor, Gina M. “‘As Potent a Prince as Any Round About Her’: Rethinking Weetamoo of the Pocasset and Native Female Leadership in Early America.” Journal of Women’s History 27, no. 3 (Fall 2015): 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2015.0032.

Potter, Tiffany. “Writing Indigenous Femininity: Mary Rowlandson’s Narrative of Captivity.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 36, no. 2 (2003): 153–67.